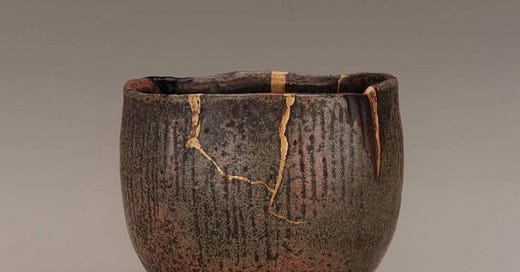

My curiosity peaked when I heard the term kintsugi, Japanese for "golden joinery."

Kintsugi is the practice of repairing broken pottery with a resin made with gold, silver, or platinum dust. The results are considered more beautiful than the unbroken item, and, over time, it became an art form.

As with many arts, a philosophy arose centuries ago that treats broken and repaired pieces of pottery as part of the item's history, thus giving it additional value.

My mind immediately flew to the possibility of a metaphor for repairing a broken human, making the breakage and repair a part of their history, therefore giving that person added value.

I ran the idea of a blog along those lines with my editor, and she asked, "Who determines who is a broken person?"

"Someone in a car wreck who is repaired physically by doctors and nurses would be one example," I explained. "Therapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists, those who mend broken minds, for another example."

"And who determines what 'added value' looks like?"

"Well," said I, "alcoholics and drug addicts who kick their unhealthy habits and become more productive citizens would be of added value to their community."

"So society determines a person's value? And the person injured in the auto accident has little value until they are mended physically? Then they become valuable to society?"

"I see the complications, but I could write about Kintsugi as a metaphor of resilience, and of the passage of time. It's related to mottainai, the avoidance of waste. People, like pottery, can be repaired and become more useful," I continued.

"More useful to whom? Does one's value lie in being whole, like a cup? Or is there an intrinsic value to a human, whole, broken, or repaired?"

At this point, I could feel a rabbit hole opening under my feet and put the metaphor of kintsugi aside until I could give it more thought, perhaps as a topic for a later blog.

And turned to Wabi-Sabi.

Anne Walther, a historian with an interest in Japanese art, stated in an article in the magazine Japanese Objects

"Related to landscapes, objects, and even human beings, the idea of Wabi-Sabi can be understood as an appreciation of a beauty that is doomed to disappear, or even an ephemeral contemplation of something that becomes more beautiful as it ages, fades, and consequently acquires a new charm."

In simple terms, it's appreciating the beauty of imperfection and the transience of all things. Some examples are the autumn leaves, the moss on a boulder, and the wrinkles on an older person's face.

Navaho rug weavers purposely put a flaw in each of their creations, as perfection is only in the spiritual, not the physical.

Since I entered my penultimate decade a couple of years ago, I have come to appreciate the impermanence, with age, of my physical and mental abilities.

I'm still working on the beauty part.

The SUNDAY MORNING TV SHOW had a piece on kintsugi, maybe you could get more insights and ideas for defense of your article from that resource.

Wabi Sabi is acceptance of impermanence, which we are surrounded by and are oblivious to. Buddhist tradition brings awareness to impermanence and an appreciation for accepting and living a happy life in its presence. Two wonderful topics Tom, thank you.

👍👵❤